Believe nothing, trust no one: ‘Morgan Freeman’ sends a message to fintech professionals

There’s evidence that deepfakes are being used to commit fraud in the financial markets. And as scam artists become more tech savvy, financial firms will need to quickly employ new tools to protect their assets.

You know his voice, you recognize his face.

He’s played the American President (twice) and the South African President. He’s driven Miss Daisy, and ridden horseback with Clint Eastwood. His silky voice has narrated Andy Dufresne’s crawl to freedom, and the Emperor penguins’ annual march to their breeding grounds. He can earn $10 million per movie, and up to $1 million just for a voice-over on a TV commercial. So it was surprising to see the actor Morgan Freeman in a sub-one-minute monologue video online. Was this a new ad for Turkish Airlines? Visa? Perhaps a new Super Bowl lip-synch battle with actor Peter Dinklage?

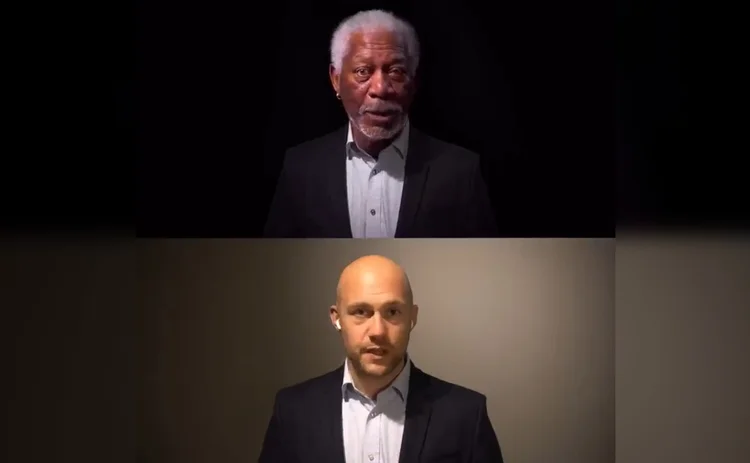

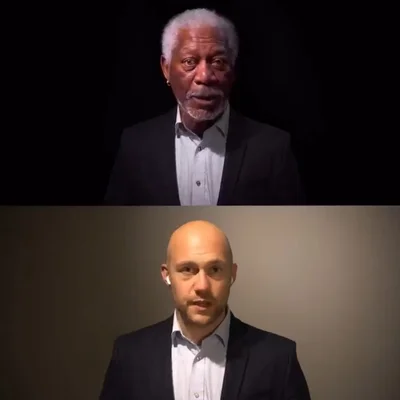

No, and even more surprising, his first words were “I am not Morgan Freeman. And what you see is not real. … What if I were to tell you that I’m not even a human being? Would you believe me?”

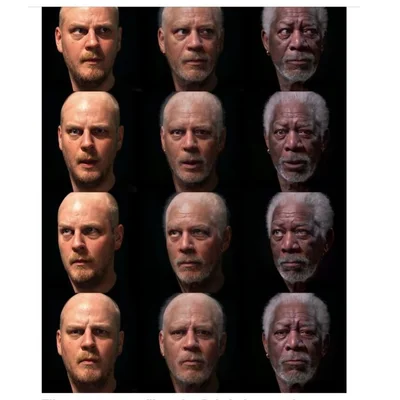

My first instinct was “No—Morgan Freeman is messing with us.” But in fact, the video was an ingenious project created by Bob de Jong, a Dutch filmmaker and deepfake creator designed to challenge peoples’ perceptions of reality in a digital age, where it’s possible to create “synthetic” people using AI and digital imagery. If you watch the video, you’ll see that de Jong has included the original footage of him reading the speech below “Morgan Freeman.” He took that video, and digitally grafted layers over his own face to create a lifelike representation of Morgan Freeman following exactly the movements of de Jong’s head, face, and lips. The two look nothing alike, yet he captured Freeman’s facial features and expressions—down to the details of how one eye is always wider than the other—to a tee. While some experts say they can recognize the video as a deepfake because it’s “too clear” at full-screen size, to the uninformed naked eye, it appears real.

And that’s part of the problem: humans don’t generally identify facts at a pixel or voiceprint metadata level. So while the Internet of Things has exposed a plethora of network-connected devices, such as printers, as easy-to-open backdoors into a firm’s confidential systems and data, the biggest single point of risk and failure when dealing with cyber crime is the human element: You know his voice, you recognize his face. And while you don’t believe everything you hear on the news or read on Facebook, you trust your senses.

So what if his first words had been “I am Morgan Freeman. And I endorse Donald Trump for President,” or “I’m here to promote this new crypto token”? These might be easy to fact-check, but it’s also likely that a believable deepfake could influence elections or money flows.

Or, what if the face had been that of your boss on a Microsoft Teams or Zoom call, instructing you to wire a payment for a supposed M&A deal, or to change security settings on an important piece of corporate IT? Or, in an example relevant to my line of work, “Hey Max, it’s Tony. Just a quick call ’cause I gotta run, but look, you know how you were going to write about Company X and the new OMS they’re developing? Between us, I hate them, their CEO is an a-hole, and I don’t trust a thing they say. But you know who is interesting? Company Y—you know, the one that does really convincing deepfake videos? They’re working on some cool stuff and we should write about them. Anyway, just between us, OK? I appreciate all that you do. Gotta go, bye.”

Now, first of all, that has never happened to me. And second, I’d know it was a fake because (a) Tony is a man of great integrity and would never ask me to do something like that, and (b), Tony is also a vicious a-hole who would never sign off saying he appreciates anything I do. (Deepfakers take note—Tony’s preferred sign-off is a one-finger salute).

But if it did, I wouldn’t be the first to be fooled. Last year, our colleagues on Risk.net reported how in January 2020 the manager of a branch of a UAE bank approved a $35 million transfer of funds after receiving a phone call with instructions from the bank’s CEO—at least, he recognized the voice and believed it was the CEO. In fact, the call came from a thief who used voice-cloning technology to imitate the bank’s CEO. The “CEO” instructed the manager to transfer funds to several accounts as part of an acquisition being handled by a lawyer named Martin Zelner. The manager then received supporting emails from this fictitious lawyer, containing instructions and what appeared to be a letter of authorization signed by the CEO.

What’s interesting about this case is that there are plenty of AI programs available (some free of charge) to deepfake a voice, but most require you to record your voice for hours to generate a convincing imitation (some newer ones only require a few minutes of recording, but require you to read specific passages for the program to successfully map your voice—and even then, the intonation doesn’t always sound natural). But while there are days’ worth of Morgan Freeman’s voice available to train an algorithm—though in his case, the voice was actually performed live by renowned Dutch voice-over artist and Morgan Freeman impersonator Boet Schouwink—there may be less audio readily available of a company’s CEO. Yes, there might be recordings of financial results, analyst calls, or TV interviews, but would these be suitable inputs to clone a voice? Apparently so.

This technology may not yet be sufficiently advanced to stand up to heavy scrutiny, or to conduct a full two-way conversation in real time that would engage and respond to a skeptical would-be victim. But with the speed of technological advances, and with bad actors doubtless thinking hard about how they can use it to their advantage, that can’t be far off.

When I brought up the topic with a senior trading technology exec lately, they said, “It’s certainly fascinating, but I can think of a ton of nefarious uses,” compared to perhaps single-figure instances of potential legitimate uses (such as, filling in mistakes in a Morgan Freeman movie, creating a customer service bot in the image of Morgan Freeman, or allowing him to license his own likeness for, say, recording commercials for which he doesn’t feel like actually turning up in person).

But the scammers will have some hurdles to overcome: technologies developed to monitor compliance in work-from-home scenarios are in theory sophisticated enough to combat these ruses.

For example, the facial recognition technology developed by UK-based vendor Citycom Solutions—originally created to ensure compliance on video calls while working from home, such as confirming identity, recognizing other people in the background, and identifying any non-compliant items or behaviors—maps 78 points on a person’s face, and can confirm an individual’s identity regardless of hats, beards or masks with 99.9% accuracy, then combines that with voice biometrics and other factors such as a biometric pattern of an individual’s keystrokes. The facial recognition is so granular that it can detect a person’s blood pressure and heart rate, whether someone is lying based on their iris size, and whether someone is a “live” person or a synthetic recreation based on muscle movements and “natural” reactions, says Citycom founder and CEO Mark Whiteman.

Other fraudsters believe trusted credentials are more effective than a trusted face or voice. One of the areas monitored by digital identity security software vendor WireSecure is “social engineering”—where, instead of a hacking or phishing scam designed to yield single, short-term results, a fraudster targets specific executives, compromises their email accounts, and then … does nothing. Nothing but sit, watch, and learn all about that executive and their business activities, until a crucial time when an opportunity appears.

For example, says WireSecure CEO Brian Twibell, in late 2020, a West Coast US-based venture capital firm was raising money from limited partners for an upcoming deal. The LPs were aware a deal was coming up, and were expecting instructions for a transfer of funds. In November, the VC was surprised to be contacted by one of the LPs querying its instructions for the wire transfer. Problem was, the VC hadn’t yet issued any instructions: a fraudster had infiltrated the VC firm’s email and learned about the deal, then inserted themself into the process, unnoticed, at the critical point. WireSecure validates messages from trusted sources using a combination of data, device authentication, and physical identity authentication.

That’s not an isolated case, especially when LPs are represented by a crowded ecosystem of family offices and attorneys—each of whom can fall victim to social engineering. “They know the deal, the dates, the parties, and they can personalize communications using information gleaned from email or LinkedIn—for example, to ask ‘How’s the new dog?’ The fraudsters can make it very authentic and unique,” Twibell says.

Whether it’s “deepvoice,” or “synthetic humans,” or simply intercepting and diverting a legitimate message chain, today’s fraudsters are becoming more sophisticated. And IT staff are fighting an uphill battle that’s becoming steeper every day—especially as cyber risk becomes the number one concern of financial firms, according to a survey conducted last year by DTCC, while encrypted cloud provider NordLocker cites the finance industry as one of the top three industries targeted by ransomware.

As IT security professionals say, “To win, we have to get it right every day, every time. For the hacker to win, they just have to get it right once.”

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Emerging Technologies

This Week: Startup Skyfire launches payment network for AI agents; State Street; SteelEye and more

A summary of the latest financial technology news.

Waters Wavelength Podcast: Standard Chartered’s Brian O’Neill

Brian O’Neill from Standard Chartered joins the podcast to discuss cloud strategy, costs, and resiliency.

SS&C builds data mesh to unite acquired platforms

The vendor is using GenAI and APIs as part of the ongoing project.

Chevron’s absence leaves questions for elusive AI regulation in US

The US Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the Chevron deference presents unique considerations for potential AI rules.

Reading the bones: Citi, BNY, Morgan Stanley invest in AI, alt data, & private markets

Investment arms at large US banks are taken with emerging technologies such as generative AI, alternative and unstructured data, and private markets as they look to partner with, acquire, and invest in leading startups.

Startup helps buy-side firms retain ‘control’ over analytics

ExeQution Analytics provides a structured and flexible analytics framework based on the q programming language that can be integrated with kdb+ platforms.

The IMD Wrap: With Bloomberg’s headset app, you’ll never look at data the same way again

Max recently wrote about new developments being added to Bloomberg Pro for Vision. Today he gives a more personal perspective on the new technology.

LSEG unveils Workspace Teams, other products of Microsoft deal

The exchange revealed new developments in the ongoing Workspace/Teams collaboration as it works with Big Tech to improve trader workflows.