Fixed Income ESG Data: Materially Different

The ESG space is growing rapidly and gaining more attention, but one area that has been largely ignored by data providers is that of ESG information specific to fixed-income investors.

Miami Beach sits with the Atlantic Ocean to the east and Biscayne Bay to the west. The sandbar was bought in 1870 by Henry Lum and his son Charles for 25 cents per acre. After failing to turn it into a coconut farm, it was sold to Elnathan Field and Ezra Osborne, who flipped it to John S. Collins and his son-in-law, Thomas Pancoast. The beach would later be connected to the city of Miami via a wooden bridge, built in 1915.

The mangroves were eventually cleared out, the channels deepened to allow for ships to freely pass through, and soil was brought in to create usable land, according to the Miami New Times. The Miami Historical Association notes that 500,000 Army Air Corps cadets were stationed in Miami Beach to train before being shipped off to World War II. And, after Fidel Castro seized power of Cuba in 1959, “millions of Cubans poured into the area,” having a major effect on the area’s demographics.

Today it’s a beautiful resort town, teeming with both young and old looking for a good time and relaxation. It’s is also extremely vulnerable to sea-level rise. Nonprofit research firm Climate Central lists Miami as the second most-vulnerable city to coastal flooding in the US behind New York City. It’s costing the city and the state of Florida very real money already. Even though the sea has only risen by eight inches since 1950, the state is planning to spend over $4 billion “in sea-level-rise solutions, which include protecting sewage systems, raising roads, storm-water [drain] improvements, and seawalls,” according to sealevelrise.org.

Miami’s taxpayers are also loosening the purse strings to help protect the city’s future. In the November 2017 elections, voters chose in favor of the $400 million Miami Forever general obligation bond, giving their local government “the ability to borrow the money on the municipal bond market, leveraging a new property tax to pay for storm drain upgrades, economic development grants and other government initiatives.”

Only three months earlier, residents were reminded why the bond might prove useful after Tropical Storm Emily dropped seven inches of continuous rain on Miami Beach, which knocked out the power for several water pump stations, and which led to extreme flooding. The total damage is estimated to have cost $10 million for the region, according to the National Hurricane Center.

Miami’s tenuous future is just one of many examples around the globe demonstrating why investors are increasingly incorporating environmental, social and governance (ESG) data into their analysis of companies. But perhaps the greatest beneficiaries of more robust and targeted ESG datasets are fixed-income traders and portfolio managers. According to consultancy Opimas, total spending on ESG data, including ESG content and indices, will hit $745 million by 2020, up from $505 million in 2018. (See chart below)

Greenfield

Incorporating ESG factor models into the investment process has largely been the domain of equities to date, but it’s starting to creep into bonds. In 2017, the Bloomberg Barclays MSCI ESG Fixed-Income Indexes launched to address “the evolving needs of institutional investors, who increasingly aim to incorporate ESG considerations into their strategic asset allocation,” according to a launch statement from the companies involved.

In April 2018, JP Morgan launched a suite of global fixed-income indices, called the JP Morgan ESG (JESG). “The idea for the index was conceived in collaboration with BlackRock to address growing demand from bond investors looking for a benchmark that targets emerging market issuers with strong ESG practices,” the bank said at the time.

According to the bank, JESG EMBI index outperformed its benchmark by 46 basis points (bps), JESG GBI-EM by 35 bps and JESG CEMBI by 20 bps in 2018. JP Morgan expects that $20 to 30 billion will be benchmarked to its JESG indices by then end of 2019, “up from nearly $1 billion currently, driven largely by investors switching to the ESG variants of our flagship indices,” according to an internal research report seen by WatersTechnology.

Others are getting in on the game—last year, Nuveen, iShares and Sage Advisory launched ESG fixed-income ETFs.

Axel Pierron, managing director and cofounder of Opimas, says firms have been slow to incorporate ESG into fixed income because there was a dearth of ESG indices and ETFs, and specialist data vendors weren’t focused on the space, or at least, not nearly as much as they are for equities. That’s slowly changing, and as a result, these datasets can be used to bolster risk practices.

“In the bond market, you have less coverage compared to the equity market; that’s why the market has been largely left outside of the analysis,” Pierron says. “What we have found, though, is a lot of interest from asset owners, especially insurance companies, on the ‘E’ side. Insurance companies believe that there will be an impact from global warming and that as insurance companies, they will have to pay for environmental disaster. So they’re now seeing an opportunity to use their investment to drive change.”

[READ: For a deep-dive examination of how investment firms are incorporating climate change data into their investment processes, click here.]

Fixed income is a natural fit for ESG, as both are more focused on the long-term horizon—the bond market has specific debts as it pertains to time and ESG data tends not to be real time (or anywhere close to real-time, for that matter).

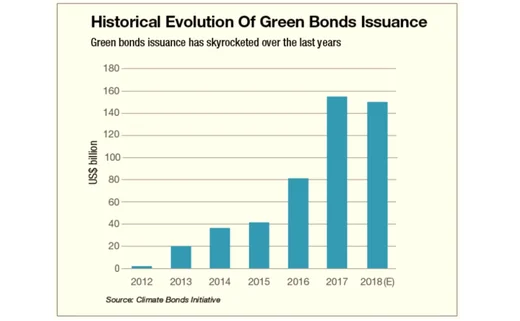

The firms providing fixed-income ESG datasets are, for now, the same as those providing ESG data for equities and it’s a field without specialists—so far. The growth of the green and social-bond markets may change that—the green-bond market exceeded $167 billion in new issuance during 2018 and it is experiencing a compound annual growth rate of 85 percent over the past five years, according to the not-for-profit Climate Bonds Initiative. (See chart below)

Yet, while there’s a hunger for information, data providers will have to better understand the needs of fixed-income investors.

Materiality

Breckinridge Capital Advisors is nestled next to Rowes Wharf on the Boston Harbor off the Fort Point Channel. Founded in 1993 by Peter Coffin, it manages over $36 billion in assets, with about $30 billion invested in the municipal bond (munis) market. It specializes in investment-grade fixed-income portfolio management, with a commitment to ESG and sustainability concerns.

Rob Fernandez, director of ESG research at Breckinridge, says the company is focused on capital preservation, so ESG data is vital to get a good understanding of its borrowers.

“We saw [incorporating ESG] as an important way to enhance our credit research,” he says. “So we’re really focused on bottom, fundamental research, on getting a good understanding of our corporate and municipal borrowers, and developing that comprehensive picture, ensuring that they’re going to repay over time. We felt that these ESG issues could have a real impact on the credit quality of companies and municipalities, and in certain cases—though it’s not broad-based—we’ve seen examples where these issues have created credit distress.”

So, what does this look like in action? The world of munis offers an example. Say, for instance, the firm is looking to invest in a water utility—it would typically gather information on water supply projections and drought conditions for more real-time data; it also looks at longer-term factors, including water supply and management procedures, as well as water quality, which is becoming increasingly important. Take, the lessons learned from Flint, Michigan, and its toxic water scandal, which was a governance (and government) problem that was exacerbated by deficient infrastructure.

“If the quality of the water is not sufficient, that’s a huge problem in terms of your ability to manage the utility successfully to generate cash flow to pay bondholders back, right?” says Andrew Teras, a Breckinridge senior research analyst, with a focus on municipal credit and analysis.

For a transportation bond, such as those issued by airports, analysts consider governance issues, carbon emissions, and if they’re located near places susceptible to sea-level rise, examples being Boston Logan International, San Francisco International or New York’s LaGuardia Airport. There are also bonds pertaining to school districts, which require more emphasis on social considerations such as academic performance relative to the income level of the population they serve—the worse the performance, the less likely that the community is going to step up and want to support payments to bondholders.

These examples show the unique challenges facing data providers in the fixed-income space—materiality is different for each investment product, and there are many investment products with nuanced considerations that fall beyond simply giving a single company an A-rating on ESG factors, as is often seen in equities.

“Materiality is constantly changing. I don’t think anyone, including us, has 100 percent of the right answers about which indicators are the most material in terms of how it ties back into credit research,” Teras says. “We’re constantly evolving in terms of the way we’re thinking about these risks. We have added quantitative and qualitative elements to the research process and we’ve taken some out when we said, ‘You know what, we tried this for a few years—we’re not sure it’s material, so we’re going to try something new.’ [The fixed-income ESG data space] is still very, very new, particularly in the muni market. So you have to be willing to try things and evolve as data becomes more and more available.”

Fernandez, who works primarily on the corporates side of the firm, says that early on when they’d think about ESG research they’d take note of how a company’s philanthropy program and where it was donating money in areas where it operates, but they wondered whether or not it had a material impact on the firm’s credit quality or credit worthiness. What they found was that it probably didn’t.

He says that the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) has been useful in helping investors to focus on key issues. As a result, they keep SASB’s framework for a particular sector in mind when examining a company. From there, analysts will incorporate MSCI and Sustainalytics reports to get a feel for what they’re saying is important for a particular company or sector.

“If you’re looking at a corporate sustainability report and they say something about carbon emissions, but maybe carbon emission aren’t particularly relevant for that sector, maybe it’s not a key issue—say, for banking—it’s more about governance and maybe social-related aspects that are the real material issues. If they’re reporting on carbon emissions and they have a plan for it and a target, and they’re making progress, that’s all really good, but that might not be what the analysts should really be focusing their time on. Whether they cut emissions or not may not have a real material impact for them, where it would for a company in the energy sector, or a company in retail that has a real, large-store footprint.”

(Story continues after BOX.)

SLOW BURN

Launched in 1971 during the Vietnam War, the Pax World Balanced Fund was created to “provide an option for largely religious investors looking to avoid direct investments in the supply chains for Agent Orange on moral principles,” according to Bailard’s Townsend. That was followed by the First Spectrum Fund, which was launched the same year and which promised to examine how these companies performed when it came to the environment, civil rights and the protection of consumers. In 1972, the Dreyfus Third Century Fund was launched with $25 million under management, a substantial sum for that time, he says.

These marked some of the first moves into the world of socially responsible investing (SRI), the precursor to ESG investing. Even though it had been around for decades by the time that Townsend entered the investment world, SRI investing was fairly-well mocked on Wall Street. “It was just a lot of upstream hand-to-hand combat on proving you could balance social and environmental objectives with your financial objectives,” he recalls. “It sounds like a simple thing, but a lot of folks had to work really hard against what Wall Street and the investment management world was saying with a big megaphone, saying: ‘Don’t do this! It will cost you money!’”

He remembers that building a simple S&P 500 portfolio where you’d avoid certain products was assailed. “Because we didn’t have a sort of greedy or alpha-seeking kind of thesis, it was anathema to a lot of folks in the financial services world and we had to manage against that for years. Now, it’s very different. Because the ESG framework has provided this kind of risk backdrop, it now makes more sense [to incorporate these metrics] if you’re a long-term investor,” Townsend says, pointing to the Exxon-Valdez spill in 1989 as being an early turning point, which led into the climate change discussions that hit in earnest in the mid-2000s. By the time of the Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010, the incident only served as a reminder of the importance of incorporating ESG into a portfolio.

Like Townsend, Boston Common’s Steven Heim has also been in the SRI space for three decades. Back in 1988, he was going to libraries and going through law books to find companies with discrimination cases. He received computer printouts from the US Department of Defense on defense contracts. He was filing Freedom of Information Act requests with the Environmental Protection Agency to find enforcement actions. While there’s still a lot of research involved when incorporating ESG, the data market is vastly different today.

He notes that a big reason why people are taking sustainability more seriously is because investors, during earnings calls, are increasingly bringing up the topic and expect detailed answers.

“Years ago, I talked with a CEO of a major housing company and he told me that no one ever asks any questions about sustainability on their quarterly calls, ‘So we spend all of this time working on these reports but no-one really cared.’ I think that that’s where it gets to how much Wall Street is actually using it for making buy and sell decisions and that will help it move more toward the investment world, rather than just being compliance,” Heim says. “We have big asset owners that now want to have ESG [analysis] incorporated.”

A Concoction

Blaine Townsend has been involved in the sustainable investment space for three decades, first as a journalist writing about corporate social responsibility and then, starting in 1991, as an investor. Today, he is director of sustainable, responsible and impact investing at Bailard Wealth Management, which was founded in 1969 by the late Tom Bailard and is located 30 minutes south of San Francisco.

The ESG data space was quite different back when Townsend got his start in 1991 at Muir Investment Trust. Once per month, he would receive a floppy disk through the mail. He can’t recall how long it would take to load the massive dataset onto his computer, but it was certainly enough time to go and get a coffee. Some of the information included in the report had been contributed by Townsend, himself. The data collected was qualitative and it was acquired, usually, through conversations with individuals, rather than through a tech-based platform.

“We’ve shifted now to this incredible world of, really, a quantitative framework for ESG investing,” he says. “I’ve seen this arc from really qualitative, hands-on [information] to this explosion among institutional investors who demanded a different level of data granularity, to now having this myriad of choices to sort through and synthesize. The more information that’s out there, the more efficient the markets for everybody, and that includes ESG issues.”

Bailard has its own proprietary scoring system called ESG Capture, about 40 percent of which is comprised of scores derived from providers of broader ESG scores. Those outside scores give them some sense of relativity between sectors for, say, the environmental impact of a consumer company, versus an energy company, versus a financial services company.

“That’s what the major providers are really good at doing: giving that kind of sensitivity analysis by sector,” Townsend says. “But then we have six different independent variables that we’re building in to go with those off-the-shelf scores—let’s call them deep scores.”

As an example, Bailard has found that corporate governance is very important, but then there are factors like political influence and contributions, schematic environmental business lines, gender-lens issues, and how the company is adjusting to climate change. For the latter, they have a factor called Climate Gap, which measures, for instance, if companies are setting goals on reducing carbon emissions. They’ll also dig into the datasets provided to them by the vendors to try and find key performance indicators for materiality.

Townsend sees the growth in the green and social bond markets—using debt to fund things that have a positive social and environmental impact—as an indicator that fixed income is ripe for ESG data growth. It’s a great way, he says, to use instruments available in the capital markets to fund infrastructure projects and ESG data can also help manage risk.

“Fixed income should really be a sweet spot for ESG, because when you think about ESG, we look at ESG as a way of positioning [corporates and munis] for the world that we’re heading into, and a lot of that has to do with risks, right? Risks that are coming our way with respect to natural resources, scarcity, exploitation of human labor and supply chains—the whole host of things that you can surmise from this data that is being constructed. So what we’re really trying to do is build portfolios that are positioned for that world. When you think of debt, what is the biggest risk in debt investing? It’s default. So anything that can enhance the credit quality and risk analytics of fixed income should be a real boon.”

It’s also important to remember that this is a nascent space and, as such, there will be mistakes made and lessons to be learned. The story of the Mexico City Airport Trust (MexCAT) bonds, which are all green bonds, can highlight this point best. On Oct. 29, incoming Mexican president Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador stated that he would cancel the new Mexico City airport, which is what the bonds were helping to fund. His announcement led to a massive sell-off, which dragged down many ESG indexes.

This shows that, for all the data in the world, political changes can still wreak havoc on fixed-income portfolios.

A Changing World

On February 7, 2019, US Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and US Senator Ed Markey (D-Mass.) unveiled their outline for what is being called the Green New Deal, a play on the famous jobs-creation program rolled out by President Theodore Roosevelt during the Great Depression. The proposal aims to tackle both economic inequality and climate change. While it is quite vague at this point, and has not been brought before Congress, it is clear that in the lead-up to the 2020 US presidential election, climate change and sustainability will serve as major talking points.

Across the pond, Europe has long been the leader in proactively using governmental and local resources to address ESG-related issues. Asia has been on the rise—most notably with Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF), the world’s largest pension fund, deciding in 2017 to dedicate 10 percent of its stock holdings to responsible investments—but still has ground to make up.

Beyond government officials getting involved in climate change, even militaries are realizing the challenges that climate change presents when it comes to national security and human migration. The US Army Corps of Engineers notes that it has “very high confidence” that global mean sea-level rise could range from a minimum of eight inches to more than six feet by 2100. “Many of the nation’s assets related to military readiness, energy, commerce, and ecosystems that support resource-dependent economies are already located at or near the ocean, thus exposing them to risks associated with sea-level rise,” it said in a report.

Furthermore, investors have come around to the idea that incorporating ESG factors can be beneficial to the bottom line. In 2015, Harvard Business School published a study which found that firms with high performance on material sustainability issues, as prescribed by the SASB, realized an estimated 3.39 to 8.85 percent annualized alpha improvement over firms that did not rate high by those standards. It’s one of numerous studies that point to better returns for firms that rate highly in terms of ESG.

And one needs only to look at South Florida to see that climate change is taking a toll on both taxpayers and insurers—and, thus, will increasingly be factored into fixed-income risk analyses. The 2017 hurricane season proved to be the most costly in US history, with damages exceeding more than $200 billion, led by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria.

In the capital markets, there’s still much room for growth when it comes to ESG data. Steven Heim, director of ESG research at Boston Common Asset Management, which is dedicated to financial returns on social change, notes that the data world for these factors still needs improving.

“Unfortunately, a lot of the [data] quality is very poor, so you still need people who can dig through this information and provide judgement,” he says.

Part of the problem is that, despite the ESG field being wide and varied, there isn’t a lot of competition when it comes to data providers. The biggest vendors dominate the space and even the specialists aren’t great at delivering more customized reports and datasets around material factors that the firm has identified—so it’s up to the firm to do a lot of the heavy lifting.

While Boston Common subscribes to different data providers for ESG research, it still has to “triangulate” that information to find common themes with what is being presented in those datasets from its own in-house research teams, to see where they agree and where they disagree. So, the ESG space—and this is beyond fixed income, as Heim says this is an issue for equities, but can be extrapolated out to other asset classes—has room for growth and improvement. But fixed income is a logical place for advancements to be made.

“It will be very important going forward,” he says. “I think there’s so much more money that could be in the debt securities [market] that it will see more attention.”

Further reading

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@waterstechnology.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.waterstechnology.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@waterstechnology.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@waterstechnology.com

More on Data Management

New working group to create open framework for managing rising market data costs

Substantive Research is putting together a working group of market data-consuming firms with the aim of crafting quantitative metrics for market data cost avoidance.

Off-channel messaging (and regulators) still a massive headache for banks

Waters Wrap: Anthony wonders why US regulators are waging a war using fines, while European regulators have chosen a less draconian path.

Back to basics: Data management woes continue for the buy side

Data management platform Fencore helps investment managers resolve symptoms of not having a central data layer.

‘Feature, not a bug’: Bloomberg makes the case for Figi

Bloomberg created the Figi identifier, but ceded all its rights to the Object Management Group 10 years ago. Here, Bloomberg’s Richard Robinson and Steve Meizanis write to dispel what they believe to be misconceptions about Figi and the FDTA.

SS&C builds data mesh to unite acquired platforms

The vendor is using GenAI and APIs as part of the ongoing project.

Aussie asset managers struggle to meet ‘bank-like’ collateral, margin obligations

New margin and collateral requirements imposed by UMR and its regulator, Apra, are forcing buy-side firms to find tools to help.

Where have all the exchange platform providers gone?

The IMD Wrap: Running an exchange is a profitable business. The margins on market data sales alone can be staggering. And since every exchange needs a reliable and efficient exchange technology stack, Max asks why more vendors aren’t diving into this space.

Reading the bones: Citi, BNY, Morgan Stanley invest in AI, alt data, & private markets

Investment arms at large US banks are taken with emerging technologies such as generative AI, alternative and unstructured data, and private markets as they look to partner with, acquire, and invest in leading startups.